This is part of a blog series about European graphic novels. See this blog post for a small introduction.

As an European, my childhood reading was dominated by the Franco-Belgian graphic novels, of which the most renowned titles today are probably Tintin, Lucky Luke and Asterix.

But right up there in top with all of those certainly was Spirou and Fantasio.

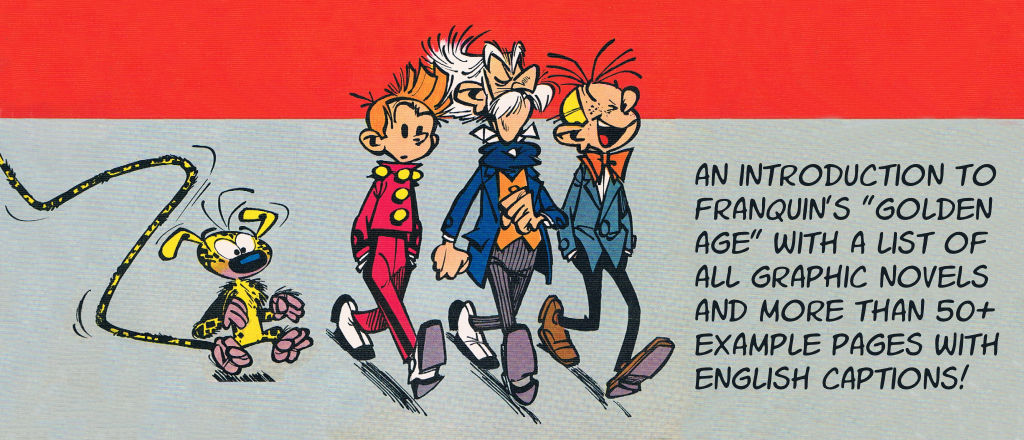

This series had amazing novels with an energy and an ingenuity that made for truly unique stories that deserve to be put up there on the golden shelf of fame. But only when we’re talking about those created by the Belgian artist André Franquin (1924-1997) and only during what I consider to be his golden age – the graphic novels from about 1950-1963.

In most of this golden age of the series, Franquin conformed to a clear line of style (Ligne claire) – much like in Tintin. Another reason why I like this period so much.

Unfortunately, the characters in the series doesn’t have proper English names. I’ve always been used to the shorter Danish names, but for this article I’ll keep referring to the original French names.

The beginnings

Spirou was actually invented back in 1938 by Robert Velter. The eponymous protagonist was originally an elevator operator at a hotel together with Spip, a pet squirrel. Right from this beginning Spirou wore a bellhop uniform that would become a hallmark of the entire series – kind of like Donald Duck always wearing a sailor shirt and cap.

It’s quite ludicrous and definitely affects the first impression negatively, but the later stories by Franquin are so excellent that I quickly learned to turn the blind eye to it.

In 1943, the series was continued by Joseph “Jijé” Gillain, who invented Fantasio, Spirou’s best friend. André Franquin took over the series in 1946 as the third artist. The first stories were full of action and humor, but it was not until about 1950 that Franquin really found his style. New regular characters were soon introduced, fantastic inventions created ahead of time, and the stories became fascinating.

For me, this lasted up until about 1963 after which Franquin gradually moved towards a more intricate, rubber-like style. The last story about “baby”-Zorglub in Champignac felt like he had lost the lightning he once had in a bottle – I don’t really consider this graphic novel part of his golden age.

Luckily, he rediscovered a new kind of ingenuity for his other gag-a-day series, Gaston Lagaffe.

Franquin decided to spend more time with Gaston Lagaffe, passing on the pen for Spirou . A lot of artists has since been writing for this series, but I don’t feel that anyone else have been able to capture the magic that Franquin once did. Another bleak change was that Franquin didn’t allow them to use the fantastical pet Marsupilami, and it was sorely missed.

The characters

As soon as Franquin took over the series, Spirou and his friend Fantasio were pretty much always reporters. Unlike e.g. Tintin, the duo often talks about having to go somewhere to do a story for the magazine and this drives a lot of the novels.

Initially, Spirou even seems to be a bit like Tintin. The kind-hearted adventurer, naive and curious, but also ready for a fight if need be. His friend, Fantasio, might give a similar first impression too, except for the fact that he looks quite a lot like a blond clone of Dagwood Bumstead from Blondie.

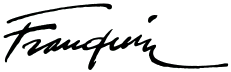

First impressions can be deceiving though. During the golden age of the series, both protagonists actually have a short fuse and sometimes even get into trouble because of it. It doesn’t take much to provoke them and then they will let their fists speak.

Yes, these are the good guys – but they definitely won’t put up with anything.

Given the simplistic beginnings of Franquin’s version of the series in the late 40’s, Spirou and Fantasio could easily have ended up being mere clones of each other. Luckily, Franquin soon tweaked Fantasio’s behavior. He becomes slightly more irrational and choleric, and he easily bursts out laughing in a loud manner.

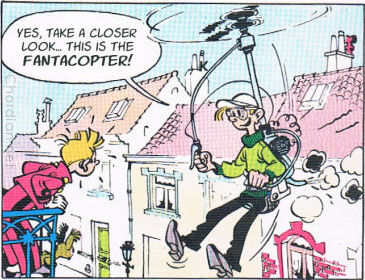

He also becomes a bit of an inventor to begin with and even constructs a mini-helicopter that can be worn like a backpack. But as the duo meets the brilliant Count of Champignac, Fantasio’s inventions quickly fade into the background. The count takes over, presenting even more wondrous ideas to aid the stories.

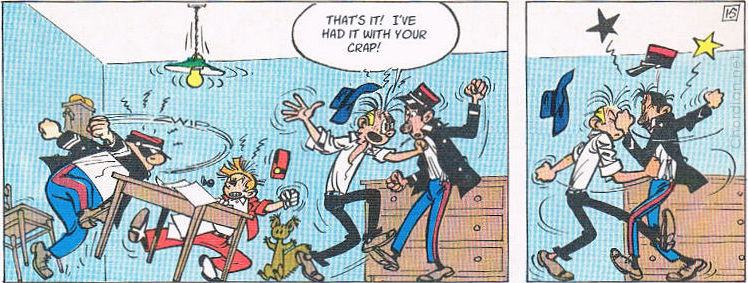

Spirou and Fantasio meets the Count of Champignac in the novel There is a Sorcerer in Champignac from 1951, which also marks what I consider to be the beginning of Franquin’s golden age of the series. The Count lives in a manor in the small town of Champignac and he is clearly modeled after Einstein. He is erudite, brilliant, and has an affinity for growing and using mushrooms for fantastical potions. Later, he also proves that he is just as adept at inventing electronic devices.

Two pets also accompanies the protagonists during the golden age.

One is the often grouchy squirrel Spip, who is a trusty companion that exists even way before and after Franquin’s work. Most of the time it merely offer thoughts as an extra dash of humor. It’s rare that it actually has any value other than that. In fact, I personally never took much notice of Spip.

As soon as the Marsupilami enters the arena (starting with Spirou and the Heirs from 1952) it completely overshadows Spip and becomes probably the most fascinating element of the entire series.

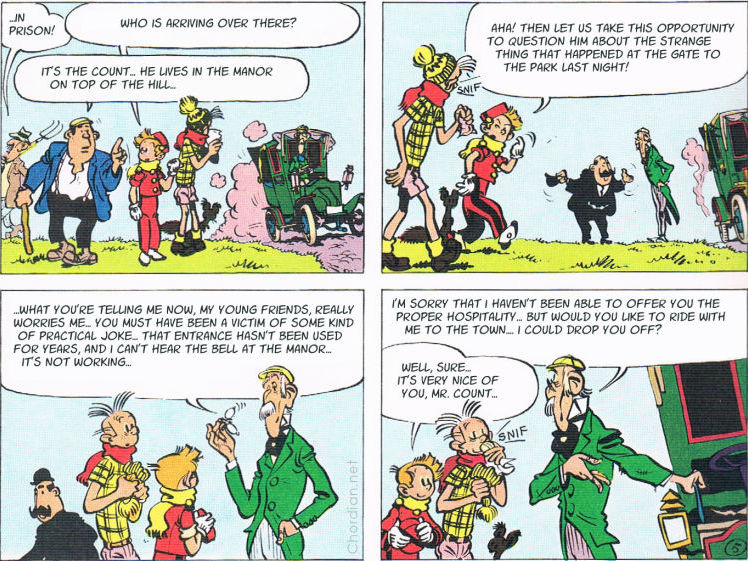

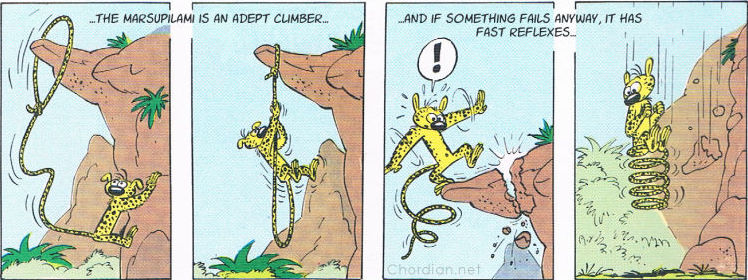

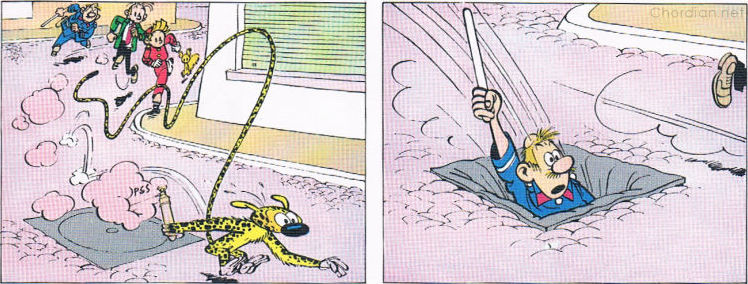

Marsupilami looks kind of like a yellow monkey, spotted like a cheetah, with a big nose and an extremely long and flexible, rope-like tail. This tail helps the wily animal overcome even the toughest odds in marvelous ways that repeatedly demonstrates the resourcefulness of its creator.

If only nature really had invented such a creature.

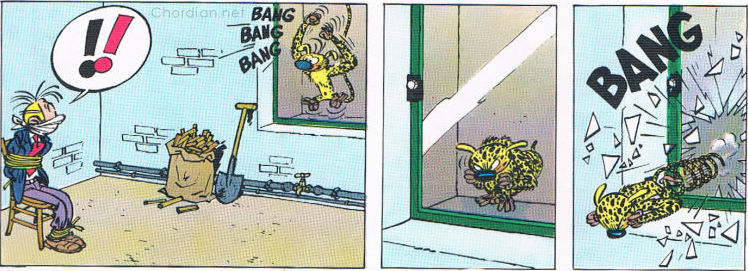

The tail can be knit at the end to form a fist for fighting – a defensive ability Marsupilami actually uses quite a lot. It can also form a big coil for jumping around, hold on to a branch in a tall tree for swinging, wield a lasso, and push against barriers to break them. The possibilities are almost endless, and Franquin always manages to come up with an impressive array of examples whenever it’s present in a novel.

In fact, the creature is so captivating that the few novels where Franquin decided not to include it actually suffer from its absence. It’s so fascinating to see what it might do in a given situation, whether to defend itself or just because it wants to have fun.

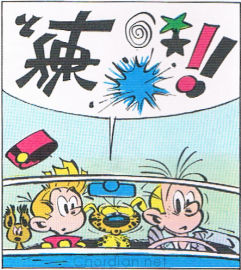

That being said, there’s no question that the animal is severely overpowered and Franquin couldn’t help adding too many fantastic abilities to it. The long tail is awesome as it is already, but during the series the pet also turns out to be amphibious, is immune to the zorglonde (more about that later), can create a nest that mechanically closes against predators, and it even repeat words like a parrot.

Especially the parrot part was probably a tad too much.

Among the many less recurring characters, three of them deserve mentioning here. These characters, the Count of Champignac, and Marsupilami were all created by Franquin.

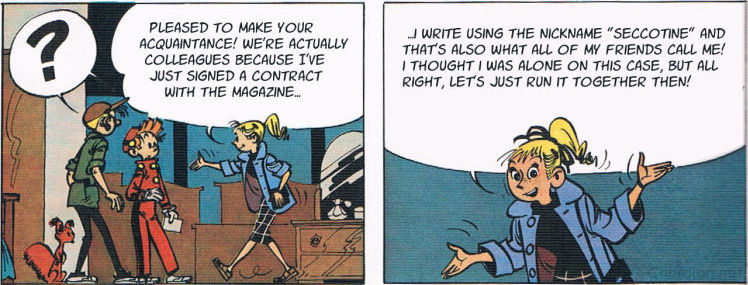

The first is Seccotine, a strong-minded female reporter and usually part competitor, part collaborator. She’s also the one that presents the documentary about the wild Marsupilami. Her appearance is often a frustrating experience for Fantasio because of their rivalry.

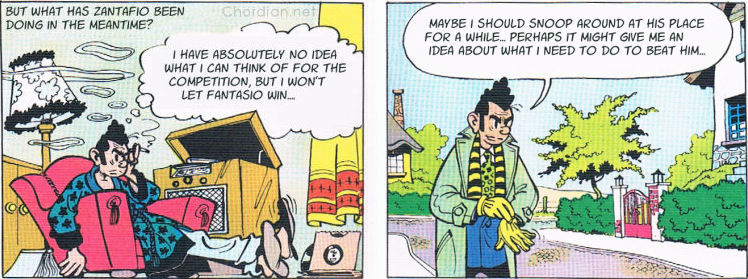

The second is Fantasio’s unsympathetic cousin, Zantafio. He is predominantly an antagonist (even a dictator in one novel) and usually a lot of trouble for our duo whenever he pops up.

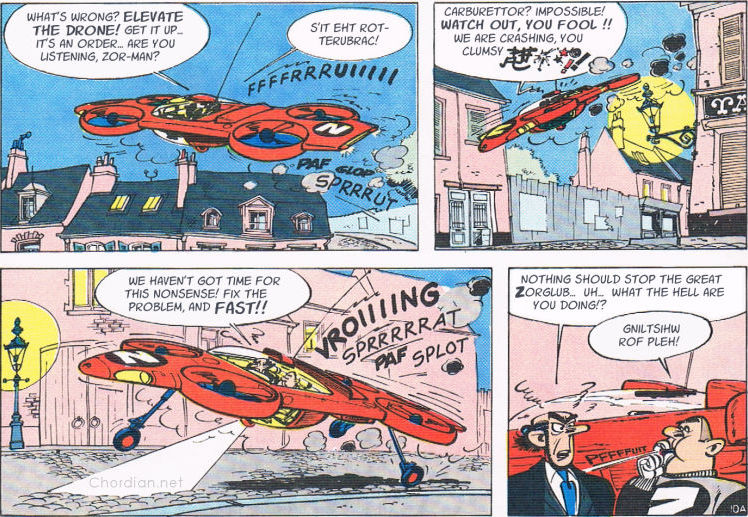

And finally there’s Zorglub, a megalomaniacal scientist that arrives in a novel with a fully fledged army of hypnotized minions and impressive inventions such as futuristic drone planes. Minions wear a gray uniform and usually speak English spelled backwards.

His greatest invention is the zorglonde, a beam that can hypnotize or stun.

Although inclining towards being an antagonistic arch-villain, he later turns out to have his moral boundaries. Eventually he is even reformed to be friends with the Count.

The inventions

Apart from Marsupilami, Franquin also had a knack for employing a lot of stupendous inventions during the golden age. This became another hallmark of the series. Some are of course implausible and only work in the context of the comics, such as the potions concocted by the Count of Champignac.

But some of the mechanical gadgets are actually quite clever and exhibits a talent for designing devices that could actually work in real life too. Some were even completely ahead of their time.

The Count of Champignac uses his mushrooms to concoct potions for e.g. super-strength, changing the speed of ageing, and resisting water pressure. He even creates a pink spray that makes metal soft like a cloth, which makes for a lot of hilarious situations.

These are great fun to see utilized in the novels, but it’s all pretty much fantasy.

In Spirou and the Heirs from 1952, Fantasio competes with his evil cousin Zantafio to win the honor of inheriting from an uncle. The first of the three trials is about coming up with the best invention. Fantasio invents a mini-helicopter that can be worn as a backpack, and it actually looks feasible even today.

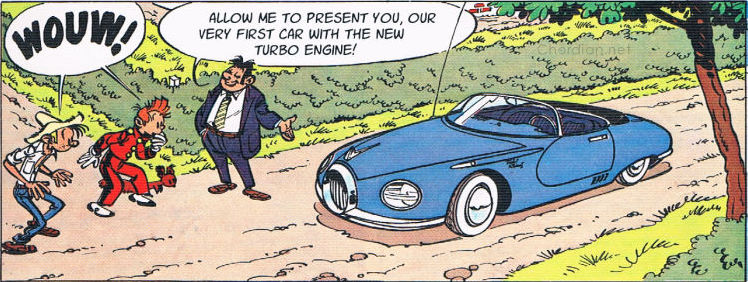

Spirou and Fantasio also manages to befriend and help two car manufacturers, and at the end of The Rhinoceros Horn from 1953, they receive the keys to a prototype of a new sports car, the Turbot-Rhino. The car has a very stylish design and almost looks like it was devised by a professional car designer.

The Turbot-Rhino becomes another hallmark of the series for many novels, until a sheik mistakenly borrows it in 1957 and smashes it to smithereens. The sheik then buys them a new white and blue Turbot car with a lot of awesome ideas such as car doors that glide into the floor of the bodywork, and an all plexiglass cabin with no blind angles.

Franquin also sort of predicted the drones that we see today, at least in the way they look. In Z is for Zorglub and In the Shadow of Z from 1959-60, Zorglub (and his army of minions) flies around in red drone planes with four rotors each. Again, they look like they could almost work for real.

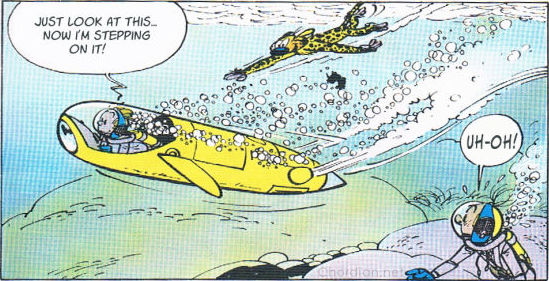

But the Count of Champignac also demonstrates that he can invent actual gadgets and not just brew potions. One of these is a diving vessel for one person, and it is surprisingly well thought out. Franquin added a lot of very logical details, such as flooding the cabin with water to withstand the great depths, and a very sensible pump-jet propulsion system.

Some of the other gadgets give the impression that Franquin could have been a great video game designer too. The beam weapon zorglonde invented by Zorglub looks like it was anticipating Star Trek and can both stun and hypnotize targets.

But the biggest shocker of them all is probably the GAG used in The Prisoner of the Buddha from 1959. This is the gravity gun in all its glory – more than 40 years before Valve used it in Half-Life 2. In fact, I’ve written another blog post about this subject alone.

The golden age is teeming with amazing inventions like these and it’s part of what makes the series such a fun read. Franquin’s talent for design and inventions, combined with the exciting stories and the numerous gags, made for a truly unique Franco-Belgian series.

Make sure to check out page 2 with a complete list of the novels and a lot of example pages.

Good read; I remember reading some of these when sitting at the comic section in the library as a kid; remember them mostly because of the Marsupilami. Good idea adding an extra note to go to page two; would completely have missed the pagination 😀 . Some of the pages you’ve picked for page 2 feel very hand picked for what you’ve written while in other cases it feels like you’re talking of very specific events, but leaving out the pages where they’re shown).

I found out with the How a French Comic Series Inspired Star Wars blog post that I had to mention the other pages specifically. Some commenters on Facebook mentioned that the pagination could be hard to spot among the share buttons, and the pagination doesn’t even show up in RSS feeds.

Cinebook has translated 17/55 of the Spirou and Fantasio books, only 38 more books Cinebook has to translate to have all 55 books in English.