This is part 4 in a 5-part series about my computer chronicles, right from the beginning of the 80’s to the end of the 90’s. I’ll go into details about the computers I used, how I got into the C64 demo scene, created my music players and editors, and the experiences I had on the way until the turn of the millennium.

Part 1 is here in case you missed it.

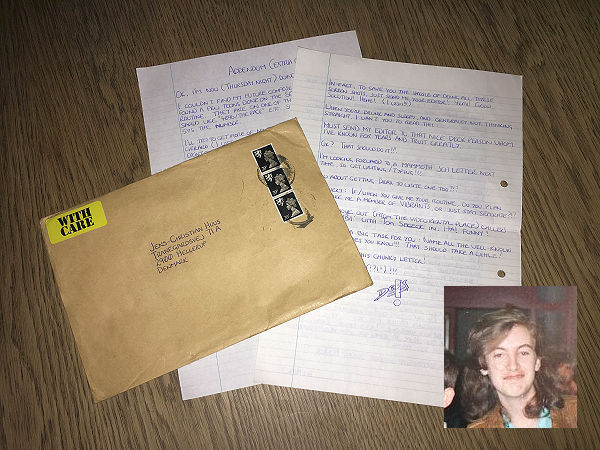

Snail mail

One of the best things about the C64 demo scene in 1988-92 was the way we swapped with each other all over Europe. Of course a ladder of recognition was in place. You had a much greater chance of swapping with the awesome guys if you had something to show for it yourself. Climbing the ladder and getting the best swapping partners meant trying to create better demos and smaller cracks. Newcomers (usually the youngest kids) that failed to impress anyone were often condescendingly called lamers.

It was something you wouldn’t want to be called, yet most of us started as one.

Being the network it literally was, getting the reputation of producing good stuff and being a nice guy earned you more connections. More people wanted to swap with you, improving the chance and speed of spreading your work. For the groups that prioritized cracks, it was about being the fastest and also having the smallest version of a game. The game might have a copy protection that was hard to crack. There was also some prestige in showing that your group can do that anyway. A smaller version meant having access to (or being able to code) a packer that could compress better than others. For demo groups, being able to break a new technical record or show a new type of awesome effect earned respect. A large part of this network was governed by this air of competition which by itself kept it alive and fast.

But the swapping also spawned camaraderie, giving it sort of a pen pal spin where nice letters were written, discussing everything related to the scene.

In my job as a postman, I loved coming home in the afternoon and check out some of the personal letters of the day. Typically there would be a floppy diskette or two, maybe along with a note and a stiff piece of carton for protection. Most of the swapping pals were impecunious and had to resort to money saving tricks such as placing tape on top of the stamps then asking you to mail them back. In spite of warning words on the envelope about not bending it, the floppy diskette would sometimes have had anything but a loving care while transported through Europe. The floppy would usually be flattened so much that it could no longer spin inside its sleeve. We had all sorts of tricks to deal with that. One was to rub the ends of the floppy sleeve against the edge of the table. Now the floppy could spin again. Sometimes we also had to use spit on the inner ring of the floppy, to make sure that the drive mechanism could get a proper hold of it. And if that didn’t help, we held down the front lock on the diskette station to force the magnetic head closer to the disk. Maybe the latter shouldn’t really have worked, but it sure felt like it did.

The word had spread in the demo scene that I had a really interesting music editor, and I received a lot of mails from unfamiliar guys trying their luck. Some just wrote a small letter using a note program on the floppy diskette instead of on paper. But as mentioned a few chapters ago, I usually gave them my music editor if I could see it was a polite request and that they offered tunes on the diskette to prove that they were actually a composer. And as I updated the music editor to a more advanced version 3, I became even more benevolent with the old version 2. Considering how much it was sent to composers all around Europe, it’s a miracle that my music editor wasn’t leaked prematurely. Eventually someone did end up leaking version 2, but at that point it was kind of all right. It was old hat by then.

Apart from the usual cracks and demos, I also built a lot of connections with composers that were interested in swapping C64 tunes. We would comment on each others compositions and offer our latest creations, some even as work tunes for your ears only. And a few wrote really long letters. Richard from Scotland (with the handle Deek) stood out as particularly adept at this. He had a very stylish hand writing and it was clear that he loved writing these letters. There were always several pages and he usually had such interesting things to write about. Some, like Xayne from Germany and myself, were even inspired by this and started writing long letters too. Deek’s envelope was thick as a book, also containing half a dozen floppy diskettes. Receiving these kinds of luxury letters from composers all over Europe became so addictive, I actually got downright disappointed if I came home from work and found that no one had sent me anything that day.

But Richard had even more than that going for him. England released a lot of good C64 games at the time and Richard was connected with a guy that was involved in delivering music for some of these. We actually got a few tunes on a few select ones. They were not the most fantastic games, but it was something at least. Richard also turned out to be a very talented composer and became another member of Vibrants. I always enjoyed swapping with him and even met him once at a show in London. After a couple of years he lost all interest in the C64 and kind of just fell off the face of the planet. A lot of us C64 freaks are in touch with each other on Facebook today, but not Richard. I have since figured out that he started singing in a few bands, but I have decided to respect his privacy.

A guy called Shade from Holland and I also started collecting SID tunes in 1990 on a growing library of floppy diskettes that we sent to each other. We collected everything from games and demos that we could get our hands on. Shade was quite enthusiastic and did most of the work. The collection grew to be reasonably adequate (certainly much more than most personal collections) but then it kind of just died out with no one to take over.

Luckily, another group of SID fans then started the High Voltage SID Collection which would soon dwarf our collection. I joined their internal mailing list around the turn of the millennium for a brief period of time. The discipline there was fascinating to watch. Even the smallest details were seriously discussed and sometimes came to a vote. As I left the mailing list again a while later, I knew the ongoing collecting of SID tunes was in good hands.

Fun and games

The following year, 1990, became almost as busy as 1989 – with a lot of work for games and visiting no less than four copy-parties as well as another show in London.

My musical friends and I made a lot of tunes for demos in my music editor, and several other guys around Europe did the same. I had made a program to select and play packed tunes called the Delux Driver, which would show the notes lighting up keys on a keyboard. This was included whenever we sent new demo music to each other. But as offers popped up for making music for games, unique demo screens were made instead where the music was presented in a small list for that particular game. It served as a demo for the coders of the game as well as an advertisement for others. Maniacs of Noise made this custom popular and it was blatantly copied by everyone else, ourselves included.

Probably the most interesting work I ever did for a game was for Orcus.

Haydn Dalton, a graphics artist in England, started working on this side-scrolling shoot’em up for C64 with Mike Ager as the coder, and they wanted me to do the soundtrack for it. The orders for it came in bits as the game was developed. I had created a separate sound effects player and editor that worked in a different way than a music player, making it easier to produce weird sliding and arpeggios. I even tried to make ring modulation emulate human speech to sound like saying “Get Ready” and “Game Over” at the appropriate moments. To my knowledge, it was something not even the renowned sound effects expert Charles Deenen from Maniacs of Noise had tried to do.

The usual basic tunes like the title and hiscore were actually not all that great, but the level tunes needed to have a limit of about half a minute each, and for some reason this limitation inspired me to be more daring. I tried all kinds of crazy stuff and most of the time it paid off. I made a tune with four-fingered chords, something I usually never did (I normally used just three). Another tune used ring modulation to sound almost like saying “give it up” and in other tunes, aliens were talking. I even had a boss tune based on a silly bass melody that my brother and I used to prank around with.

Unfortunately, Orcus became another one of those that were never finished. It was a real shame, given the amount of work I had put into it.

Speaking of Charles Deenen, I actually had a brief exchange with him per snail mail. He was getting too many orders for him to handle and was looking for qualified help. I sent him a floppy diskette with some of my tunes on it, but the first reply from him was not welcoming. He was all business and mentioned something about the English market not wanting the “hit, snare” kind of music and that I should listen to what Tim Follin had done. But at the same time he encouraged me to try again, so I did. One of the tunes I sent him on my next diskette was the intro music for Push-It, another game that wasn’t finished. Ironically the music was indeed of the “hit, snare” kind, but it was also spunky and with a double voice drum. Charles wrote back to me with words in the line of that being more like it. We weren’t accepted into Maniacs of Noise as such, but if a job came up that they didn’t have time to do, he would get in touch with me.

Push-It (Intro)

The tune that convinced Charles Deenen. It has interesting changes at 0:17, 3:09 (solo) and 3:56.

The one job that eventually did come up was the C64 conversion of the arcade racing game Chase HQ II, also known as Special Criminal Investigation. I was working on something else at the time, but luckily Link was happy to do the tunes for it. Link tried to match the typical Maniacs of Noise sound and I think he actually did a decent job at it. I had to multiplex two voices of sound effects with two voices of music to fit three voices at the same time, but in the final game only one voice of sound effects was used. One of the tunes was also skipped, and I believe Link never got any payment either.

Drax and I did get to respectively make the music and sound effects for a few games that were eventually released, but they were mostly smaller games for magazines created by scene friends in Cosmos Designs. A small Danish maze game based on a popular television quiz also had its theme converted. And again there were more work for a few that were never finished.

We were rocking the demo scene, but the game scene? Not so much.

At least there wasn’t a shortage of copy-parties to attend. The first was the Horizon Easter Party in April. It took place in Stockholm and I took a night train up there that failed to give me even a minute of sleep – it was way too rumbling for that. The Ikari guys was there, and they managed to bring Bod and Just Ice from England as well. I met Prosonix, a talented group of Norwegian SID musicians.

The second one was all the way up in Bergen, Norway. I took a plane up there to an ice hockey hall that now housed tables and wires for computer equipment, although most of the visitors piled up against the walls of the hall, or on the balconies. Apart from Prosonix, I also met Geir Tjelta and IQ64. But the most interesting memory from this party was actually when I took the plane home. The weather was awful, extremely windy with lots of rumbling the plane and air pockets. I was really anxious and actually feared for my life. Then my eyes turned to a suit sitting in another seat just a few rows in front of me. He had his head back against the pillow, sleeping like a baby.

I also attended Censor’s Halloween Party in Göteborg (Sweden) in November, and Dexion’s X-Mas Conference in Odense. In addition to the group members Drax, Metal and Link, I also talked to Scarzix, Scortia, MSK, Zonix, Kwon and the guys from the demo group Starion from the island of Amager, to mention just a few. I presented my new tune “Chordian” at the Dexion party. I think Link was the first to hear it. I was unsure about it at first, but it became both a hit as well as one of my personal favorites.

Chordian

When I first composed this, I was afraid that it was a bit too simple.

In 2006, I even decided to use the name of it as my new handle on the internet.

I also attended the ECE Show II in London in September that year. This time I went there on a ship together with Niels from Channel 42 and his friend, Henrik. The Ikari guys also went there, including Fletch’s brother Michael. I still knew nothing about London, but Michael had been there before and knew the sights to visit. Together we went from one underground station to the next to see as much as we could. I didn’t try to sell our music at the show this time, I was just there for fun. I briefly met Charles Deenen but it was merely to exchange a sentence or two. And just as I feared that we would never find each other at the show as agreed, Deek from Scotland suddenly popped up and introduced himself.

September is also the month where Laxity joined Vibrants. Gone was the antagonism we ever had, if it even existed – maybe it was just all in our heads. Laxity later even created a new player version for my C64 editor and admitted that it was well thought out.

All good things

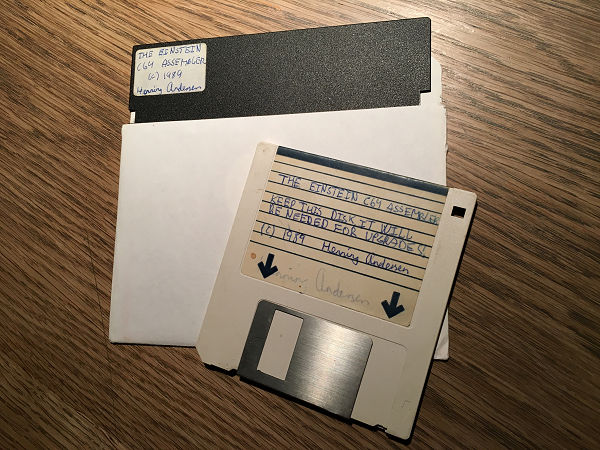

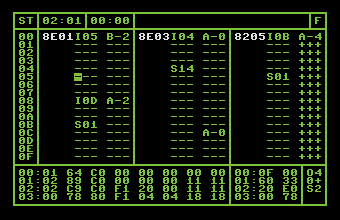

I had plenty of new ideas on how to further expand my C64 music editor, but I was running out of memory fast. The assembler editor I used, Turbo Assembler, took up some of its own and I also had to allocate a lot of space for the music player and its uncompressed tables.

What could I do about that?

Luckily, the answer was just around the corner. The brilliant demo coder Henning Andersen (Einstein of Upfront) had created a hardware solution called EASS that worked as a cross-assembler. I immediately ordered a copy of this and received a few pieces of hardware to connect to the parallel and video ports of the Amiga and the C64. The source code would now be edited and saved on my Amiga 500, making use of its higher resolution to display more characters per line. By a tap of a few buttons, the source would be compiled into machine code and then dumped into the RAM of the C64.

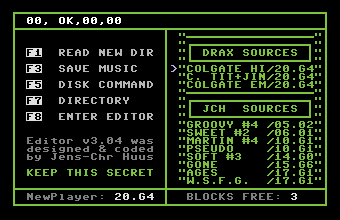

I used this development kit to create version 3 of the music editor. Among the many new features were follow-play (the channels scrolling to the music), support for quick players, tune and work clocks, a global volume, faster user interface, improved editing and of course bug fixes. I also made a superfluous poly-play feature that made it possible to play actual chords on the C64 keyboard while holding down several keys at once. But for the most part, version 3 was a significant improvement to an already renowned editor.

Coding on version 3 began in December 1990. I made a few minor version updates with small bug fixes during 1991, and the final v3.04 (that now also worked on SX-64 and C128) was done in August 1991.

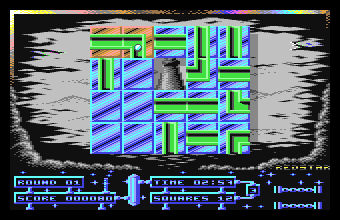

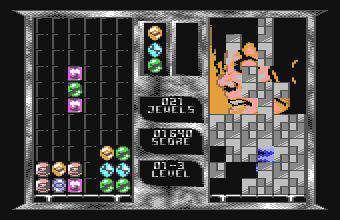

Rewinding back to March 1991, I got an order for doing the music and sound effects for a German puzzle game called Su-Sweet. There was a tight deadline and I worked on my C64 like if I had an actual office job for a few days, then sent back the lot per snail mail. It may not be my most praised soundtrack, but I was actually reasonably satisfied. The title tune was funky and didn’t sound like my creativity ran off the track. I even liked the level tunes. If I have to point at one bad thing then it has to be that the developer didn’t pick up on my intentions for the level start sounds. The preview of the game showed a phrase sliding into view, stay for a second, and then slide out again the same way. I made sure the level sounds used sliding to match that exactly, but it wasn’t used like that at all in the final game.

It was probably another good example of a lack of communication. Making music for games across long distances per snail mail had a tendency to produce unwanted compromises because of this. We were amateurs and didn’t have a strict set of rules about how to discuss such details. Most of the time, it even felt kind of like one-way communication. If I didn’t know the guys making the game, their order would sound like they had already created a lot of the game framework and thus the implementation of the music and sound effects was pretty much set in stone. Here’s what we need, period.

I remember that I was concerned about the design decision having either a full music track or only sound effects in Orcus. If I had known the creators better or been with them while developing it, I might have suggested mixing music and sound effects, maybe even trying the multiplexing stuff I made later for Chase HQ II. I didn’t like the idea of having a piece of music playing but no sound effects while shooting down aliens. It felt wrong for so many reasons. Sound effects could give you a cue of what was arriving or changing, and then a piece of music would just be like turning on a chiptune radio.

At its worst, the developers sometimes didn’t even bother to report back. I had made a quick player title tune for an adventure game called Brubaker back in January, but I was never told that the game was actually finished and released.

No thank you, no payment, no nothing. Johannes was so right about this.

Nevertheless, the work for Su-Sweet is probably the only time it really felt like a real job for a game. It was a tight deadline instead of spread over months, the game was finished and released soon after, and I actually got paid too.

However, I also learned that I didn’t really like working within a tight deadline. Some people thrive by deadlines, but I despise it. It may get a lot of stuff done fast, but I feel like I’m in the trash compactor of the first Star Wars movie. Ironically, working with soundtracks for the top games would probably have had me engulfed in deadlines. It’s indeed possible I would have hated every second of that.

I had now tried a lot of things with the SID chip since 1987, but there was still one big area of unvisited territory. Digital samples. Changing the main volume on the SID chip made a small click, and this could be used to play crude samples in addition to the normal three voices. A lot of music coders had already experimented with this. Johannes Bjerregaard. Charles Deenen. Rob Hubbard. Martin Galway. Geir Tjelta. Even SoundMonitor had a RockMonitor offshoot since before I even started coding my own music players.

Could I code something like this to work well, and where would I get the samples?

It was actually a bit of challenge to code this into my music player as it required the use of something called NMI, of which I knew nothing. I had to learn about it on the way. I was probably a bit too ambitious and added all sorts of luxury effects to the digital channel. I used an old SFX sound sampler in the cartridge port to record some synthesizer and drum sounds from my Korg M1 keyboard. Being a bit behind with samples on the C64 as I was, I decided to call my first digital tune “Better Late than Never” on June 23, 1991. I managed to compose three more digital tunes, but it was cumbersome. I had sort of hacked my own music editor to swap a voice for the digital one instead of coding it properly, so it was too hairy to be used by anyone else but me. So, no digital tunes by e.g. Drax.

Better Late Than Never

My first digi tune and player. No advanced tricks in the fourth digi channel yet.

I had begun playing more consistently on my Korg M1, but since I started learning at such a late age, I wasn’t really good at it. It was all ping pong bass and a bit of fumbling. Using a MIDI sequencer to record a longer piece was usually too erroneous to be of any good use. Still, I managed to devise some songs and harmonies in a different way than what I was used to in my C64 music editor, where things just sort of figured themselves out as I typed it in. My last tune ever on the C64 was called “Shift” and was a normal SID tune for a few minutes then broke into an additional digital track as sort of a surprise. It was composed solely on my Korg M1 before typing it into the music editor. Ironically, this first time of doing it like this was also to be the only one. It became the last tune I ever did on the C64.

Shift

I was never quite satisfied with the digi that starts at 1:16. Too messy and muffled.

Apart from an atypical exception or two – like making a crowd noise sound effect for a demo in 1992 – I pretty much left the C64 after the digital experiments. Another type of computer was waiting, offering a new kind of sound technology I was dying to check out.

That was the end of part 4. Click here for part 5.

The past starts to become future and never stop! ….Immortal C64 scene 🙂

that giv’ it up ring modulation trick is brilliant – what an unreal soundtrack – I would love to see that game finished one day – would even pay !

I actually did a couple of tests with digis but wasn’t quite satisfied with the result 😀

Geir thanks for composing the Density tune for me way back in 1990 and thanks Jens for all the chiptunes you made I simply loved Sandra’s Secret Land didn’t know it was an actual song back then.