This is part 2 in a 5-part series about my computer chronicles, right from the beginning of the 80’s to the end of the 90’s. I’ll go into details about the computers I used, how I got into the C64 demo scene, created my music players and editors, and the experiences I had on the way until the turn of the millennium.

Part 1 is here in case you missed it.

Stepping stones

1988 arrived and it would completely eclipse 1987 in activity and important events. First of all, I was jumping from one group to the next, typically together with a few friends such as Kim, to greener pastures. The first jump was from New Men to Galaxy in late 1987, then to 2000 A.D. in February 1988. After a very short stop at INXS in April, I continued to Jewels (joining up with Brian and their friends) the same month, then Wizax in June. Finally I settled down a bit with Dominators in August – at least for the rest of 1988. Most of these groups had something to do with cracks, but they had their demo divisions as well. I made a few demos along the way, like the wavy “Enjoystick!” for 2000 A.D., and I also made the last part for a disk loading demo by Jewels where I had two color-cycling scrollers across removed side-borders. Not totally out of this world, but good enough to prove that I knew more than just how the SID chip worked.

The scene was constantly growing, new people popped up in new groups, and a lot of them turned out to be allies – new friends – but not all. Some were in direct competition with me right from the beginning and stayed that way for years.

One such person was Thomas, better known as Laxity.

I first heard about this kid somewhere in the beginning of 1988 as I got a disk with a lot of his tunes in his own music player. The music player used almost no CPU time and sounded bloody great. His tunes were frisky, energetic and clearly showed a lot of talent. I was still using the OldPlayer system that munched way too much CPU time and was starting to feel somewhat archaic, and my music also felt like it couldn’t quite match up. It was like I had been cruising along on the highway with a smirk on my face, completely oblivious, and suddenly I was passed on the inside by this rich kid in his fancy sports car.

I was instantly jealous.

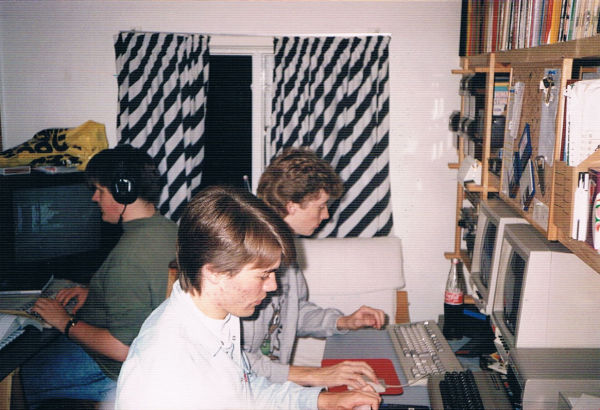

My parents lived in Hellerup a short distance north of Copenhagen, and I had a room upstairs sort of built into the attic. As the years passed by in the late 80’s and most of the 90’s, I had an impressive traffic going of teenagers from both the Amiga and the C64 scene. Coders, graphics artists, musicians, swappers, and a lot of their friends. More often than not, we were at least three or four guys on a typical evening. Part of the reason was that I had all sorts of interesting stuff available. Eventually I had several C64, a C128, an Amiga 500, a PC later, I had a Korg M1 synthesizer for many years, and I also bought an arcade machine together with a lot of arcade prints so we could swap them out. All that made it the place to hang out for for a lot of like-minded computer nerds. Some checked out the new cracks we had acquired for Amiga and C64, some broke the hiscore on one of my arcade prints hooked up to a real arcade machine out in the cold and dark part of the attic, others came by to actually share knowledge and code demos and music players.

Thinking back, it’s actually quite amazing how many of the recurring visitors were famous in the demo scene. Among computer musicians there were Drax, Link, Jesper Olsen, Johannes Bjerregaard (another one with a C64 music player in 1987), Tomas Danko, Shade, Anders Øland (who would later have a club hit with Barcode Brothers), MSK, and more. Then there were the talented creators of Hugo and Super OsWald as well as the coders and swappers from notorious demo groups, some of which I was also a member. Some came by for several days, sleeping in our guest room, others only stopped by for an hour or two and then they were off again. It was a wonderful throng.

I will get back to those in a later chapter about the Danish games.

There was one evening where my old friend, Axel, came up, took one peek into my room full of nerds, then said, “I’ll… come by some other time!” and then he left again.

When he did turn up and an Amiga was available, he played a few games and was typically one of those that were off again after a few hours. I remember there was one time where he died in a frustrating game, but instead of shouting – which wasn’t really his style in the first place – he jumped into my bedroom and started dancing to let off steam.

Anthony Quinn would have been proud.

Laxity’s player

Around summer 1988, one of the new guys that visited me together with some of his friends was another Thomas, better known as Scorpio of 2000 A.D. He immediately left a solid first impression with me. He was a talented demo coder, one of those that had ideas of how to push the envelope and maybe invent new techniques. What really got to me was the speed of which he created and tested things. In mere seconds he had created a set of sinus data using a few simple BASIC commands, which was then used in assembler to swing a logo around in elastic waves. It was like Scorpio “worked closer to the metal” so to speak, and somehow that inspired me; changed my own way of coding. I learned to stop beating around the bush like I had with my Aegis Sonix nonsense, to cut corners and try out new things.

Being damn jealous of Laxity as I was, I ran a new C64 tool I had found straight on his player that reverse engineered it into the assembler editor we coders were using. The labels were all generic, but with a bit of detective work I figured out some sensible names for them that made it clearer what was going on. I knew that Laxity was composing his songs by typing in hexadecimal numbers into a monitor, and I wanted to try out something similar. I settled with hexadecimal numbers in the assembler source and then compiling it to listen for errors. Luckily the compilation process was so fast that it actually turned out to still be quite feasible. While I was trying out a new leader for a bassline originally created by Laxity, Scorpio told me that what I was doing sounded awesome.

That was another reason why I eventually made so much music and relevant code on the C64 – all the praise I got. A lot of my friends, visiting or swapping, repeatedly commended me on my progress on both my players and my music. It was like an energy source to me. I gobbled it up like candy and it renewed my drive for creating even more.

Unfortunately that would later turn out to be a problem on the PC.

Even though I knew that hacking Laxity’s player wasn’t really nice, the praise from Scorpio and others lured me into making more tunes in it. Composing in assembler was so much faster and more efficient than the Aegis Sonix method. It was like comparing a heavy truck with a swift car. Another thing that improved immensely was creating instruments. The old player system required me to dump in all the note data in one go and then create all of the instruments in another. Not only was that anything but efficient, it also made for a lot of unwanted distortion. This problem was virtually nullified when composing directly in the assembler listing. I ended up creating a total of about six tunes in Laxity’s player.

L.L.L.

This was my first attempt in Laxity’s player. I left parts of his instruments and bassline intact.

Can’t Stop

This was quite popular in the United States at the time.

Birthday

The first 20 seconds is a conversion of a Danish birthday song.

Last One

This is the last tune I did in Laxity’s player. It changes at 0:30.

And then another copy-party arrived. It took place at a school in Nykøbing Sjælland in northern Denmark, in the beginning of July, 1988. It was just humbly called the Dexion Meeting, but it was considerably bigger than my first one. Laxity was also there and I believe Future Freak was too. They were sitting at tables on a stage overlooking a corridor while I was sitting at a table somewhere in the side, in front of the stage. Laxity and I had barely ever talked so far, but at one point he came down to me and we had a chat. Before leaving, he finished off by saying that it wasn’t a good idea that I was using his player. I’m sure he didn’t mean any offense by it, but he actually did the scene a great favor. It made me realize that I was stuck and gave me the incentive to move on.

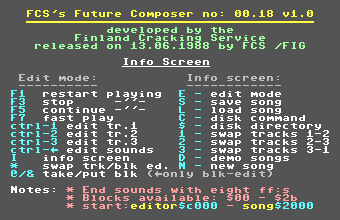

At first, however, I didn’t quite see it that way. Suddenly I was left on the highway without a ride. I started considering my options. The old player was certainly not among them. It was just an old Trabant by now. Then chance would have it that a new editor called Future Composer had just been released at the party, an editor using hexadecimal input to make music in a hacked music player of good quality. I was wondering if this was my next option. In fact, I sat down and made a tune in one of the class rooms. It was definitely interesting, but I didn’t like the way editing was done. Voices were not compared directly and it had always been one of my dreams that a music editor should be able to do that. I imagined that it would help immensely when composing. I settled with just that single tune in Future Composer, and it was absolutely the right decision. It didn’t take long before everyone and his dog was using Future Composer in demos, and just as with SoundMonitor, it became way too recognizable and thus just as trite. It became synonymous with demo coders that didn’t have access to unique music in special players and had to settle with less. That’s not an image you really wanted to have as a respectable demo group.

Typhus #1

The test tune I made in Future Composer at that party.

But Dexion’s copy-party this summer was also interesting because I believe I actually spotted another soon to be famous musician way ahead of time. Just behind me was a circular table, and a guy with thick, dark brown hair was sitting at his C64, coding what I could clearly see was some kind of music player. All the indications were there. This was his own stuff and he clearly had some skill. I can’t exactly say why, but I was hesitant in starting a chat with him. He seemed like he wanted to mind his own business. It would take many months before we would finally get properly introduced.

That guy later turned out to have been JO of Amok.

The new player

Not long after I got home from that copy-party, that same month, it became clear to me that the only viable option was to start all over. Make my own player again, although this time making use of everything I had learned from using Laxity’s. I seem to remember that Scorpio was once again visiting me and commending me for my progress. I went from a prototype version with mere bleeps to one with pulsating, arpeggio and drums using a table of waveforms, all within a sensible use of CPU time. Finally I was onto something.

Simple Tune

My first test tune in my own player. No effects yet, just pure notes.

Tuned In

My first music player after using Laxity’s now had a few decent effects.

Short ‘n’ Sad

And finally, drums.

My own player again, and this time not a Trabant. More like a Ford. Maybe a VW.

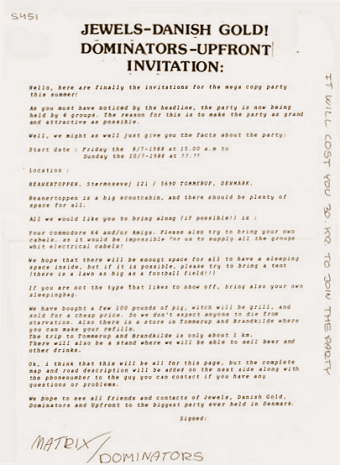

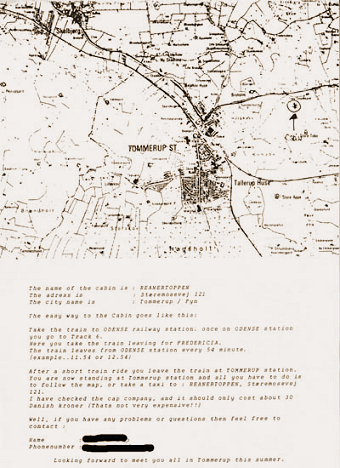

Another party came up, this time held by Jewels, Danish Gold, Dominators and Upfront in Tommerup on July 8-10, 1988. It was in the middle of Denmark, roughly speaking. I can’t remember much of the company I traveled together with nor anyone I met, but what I certainly do remember is the disaster it started out as. We arrived way too many nerds to a tiny hut next to a bumpy field where nothing seemed to have been sown. We were among the first and I quickly booked a table just inside of the hut, but more nerds arrived in several waves and it was hopeless. Before long, they were rolling out wires on the field and placing unsteady tables there to put their computers on. It not only looked silly, it looked downright surreal. It didn’t take long before the organizers knew they had to do something. Soon a few buses and cabs were summoned and we were all driven to a place with a much bigger hall. A considerable improvement.

Sleeping at copy-parties has always been one of the big cons for me. Sometimes a party had a dedicated sleeping room in another hall, especially if it was a school. Teenagers typically lost all sense of time and slept whenever they absolutely had to. Some in sleeping bags right next to their tables. Some even with their face down on their keyboard, only to wake up a few hours later with QWERTY imprinted on their faces. No matter what you did, it was almost impossible to avoid a lot of noise from hundreds of computers, stereos and people passing by here and there. Some of the later parties in the end of the 90’s took place in a town where I could book a room at a hotel. It was expensive, but absolutely worth it.

Since the party in Tommerup was one of the first ones and we still had to figure out how to nail such things properly, sleeping was quite a problem there. At one point I had to accept sleeping under a table with makeshift legs and computer equipment on top. It wasn’t too bad, actually. I managed to fall asleep and get an hour or two of shuteye. In the meantime, someone had the marvelous idea of sitting on the end of this table, and as he jumped down and walked away, the makeshift legs of the table gave in. The entire table came crashing down on top of me, computer equipment on top and all, brutally waking me up in the process. I was lucky and it didn’t squeeze or hurt me all that much, and in the instant I woke up, I knew that a hundred eyes would be fixed upon me. I slowly squeezed out and made sure that I was completely stoic. Nothing to see here. Please move on.

It actually looked like people around me were genuinely disappointed.

I continued making music in assembler listings of my player for almost the rest of 1988. In the meantime I got to know Johannes Bjerregaard, a computer musician that not only had his own player on C64 but was also absolutely brilliant on a piano. He had already made music for a few C64 games and had a great talent for both coding and composing.

I had kind of a strange relationship with Johannes Bjerregaard. There was a lot of unhealthy respect for his abilities that actually made me feel uncomfortable around him to begin with, but at the same time he was also the humble type that didn’t like to brag at all. I remember I sometimes played my C64 music for him, sort of like an eager student seeking the attention of the enigmatic expert. Most of it he didn’t comment at all (probably not a good sign) or he would point out a few disharmonic errors.

I also visited Johannes once or twice in his very tiny apartment he had in Copenhagen at the time. He had a shy cat that had lost its tail. It just sort of withered away, he told me.

He even sold me his Roland JX-3P keyboard. I later replaced it with a Korg M1.

Johannes had a wise habit of recreating all sorts of old and new radio hits as C64 songs, both to learn their arrangement and to see how close he could get. What was not quite as awesome was that he easily deleted those tunes shortly thereafter. A lot of tunes got lost this way that could have been legendary today. I actually managed to save a disk at one point from deletion, but a lot of others got lost forever. My guess is that he regarded it solely as training and thus not worth retaining. He was very critical of his own work.

I was at another copy-party in Hillerød held by Hexagon in late October 1988. Laxity and Johannes was also there. Both of them felt way out of my own league at this point. I was envious of them both. They could play the piano well, I couldn’t. They both made better music than I did. It was discouraging and this might normally have kept me from continuing any further, but coding players and making tunes was great fun and I felt committed.

I refused to give up now.

The music editor

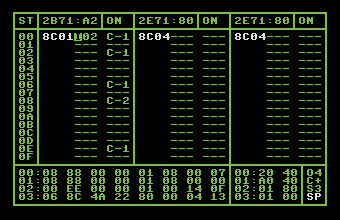

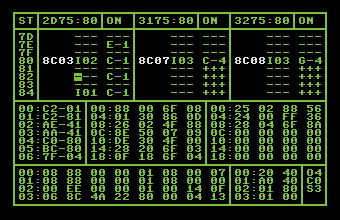

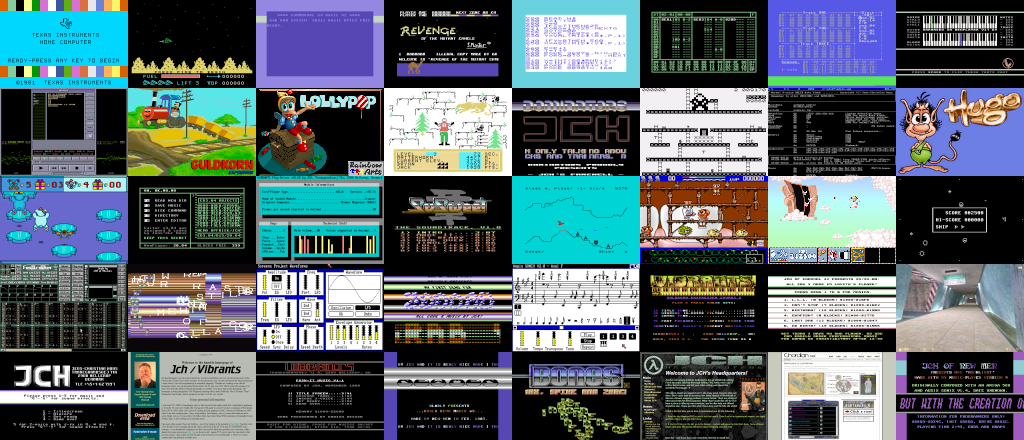

Right since the very first old player in 1987, I always wanted to have my own music editor designed to accommodate my lack of musical education. I wanted tracks to follow each other so that multiple voices could be compared easily. This was actually in my mind even before the first SoundTracker appeared on Amiga, a tracker that had four voices in columns of about 64 rows each. Notes were alphanumerical in this system, like F#3 or C-4. When it did arrive on Amiga, I tried it out briefly and made a few test tunes in it. This was definitely a step in the direction I wanted, but I absolutely didn’t like how the voices were “fused together” in the same pattern. I wanted my voices to follow each other while still having independent sequences of any size.

SoundTracker was released commercially on the Amiga by Karsten Obarski in 1987. It could edit patterns of typically 64 rows each. Channels would be shown side-by-side in rows of small steps that ensured that the music was always accompanying it precisely as the alphanumerical notes passed a cursor line. This made it great for beginners that knew little about how to compose music.

![]()

The first version used the MOD file format and had 16 sample instruments. It quickly became popular on the Amiga as the MOD files could be used in games and demos. During the following years, the tracker was disassembled and reproduced in offsprings with various improvements. In fact, the idea branched out into trackers that had their own players and file formats, yet still used the same pattern principle.

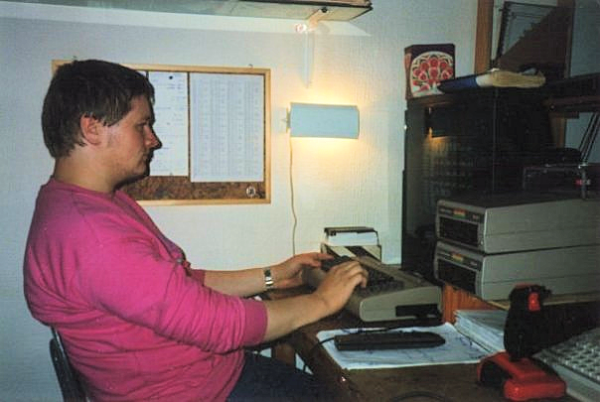

Towards the end of 1988, I started thinking a lot about how to do this. I was a postman at the time and had a small route in Rungsted, a bit north of Copenhagen. It was often boring in the sense of visiting the same houses day after day, over and over. After a while it was going through the motions leaving me time to think while working. I thought a lot about that music editor. Sometimes I got an awesome idea of how to design something and I stopped my bicycle, fetched a blank register slip out of my little black book, then scrippled a few notes for later. A lot of ideas, both for the player as well as for the editor, was conceived this way. If only I had kept these slips so I could show you here, but alas I threw them all away as soon as I had copied the notes from them.

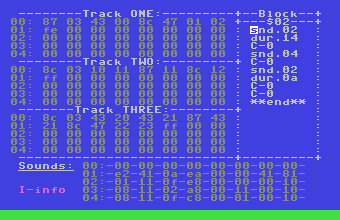

One detail of the editor design was clear to me right from the start. I wanted it to have a consistent green look, just like green graphics on really old computer monitors. I imagined it would not only give the editor a unique look, it would also be comfortable to work with. I also wanted to have all tables and other editable information on the same screen. Changing to a different screen to edit e.g. the instruments might bring me “out of the zone” of composing a tune and I wanted to avoid that. Finally, I still remembered my earlier idea of the three voices of the C64 always following each other but have completely individual sequences of flexible size. It would make it possible to repeat short pieces in one voice while still repeating the longer ones in the other. That made a lot of sense to me.

In November 1988, I started coding on the first version of this green music editor. Coding the chain of sequences for each voice seemed daunting at first, so I cut a corner and just made infinitely long voices to begin with. I made the first four test tunes in it, but it was soon clear that the lack of sequences was absolutely not okay. So in December, I recoded the voice parts in version 2 of the editor to work with the flexible sequences as originally envisioned. I made a lot of additional test tunes and it was immediately clear to me that this was a massive leap from composing directly in an assembler listing. Comparing voices and editing music in real time was so much faster. Instruments and other help tables were put in the lower part of the screen, with another half pane popping up on a hotkey, reducing the size of the editable area for the notes. This ensured that notes were always available for tweaking no matter what table I wanted to edit as well. It sped up the editing process and made it possible to really “zone in” composing music.

I named my first official tune “Revolutionary” as 1989 arrived.

Revolutionary

The first tune I did in my final version 2 music editor.

1989 is probably the year I remember as the most active year on the C64. I now had a good music player and now also an editor that was quite unique. I made a few more tunes and upgraded my players with better effects and techniques. The music was edited in big tables that was spread out to make insertion and deletion much easier to handle. Because of this, source tunes took up a lot of disk space. I then coded a packer that not only packed bytes closer and removed redundant information, it also concatenated note steps into fewer bytes with duration indicators instead. The end result was a much smaller block that was combined with the music player, ready to be used in a demo or a game. Later, I expanded the family of tools with a player version swapper as well as a relocator that could move a player block to another location in the C64’s RAM.

While working on these tools and composing more songs in the editor, I was starting to wonder how other composers might sound like in it. It wouldn’t take long before I got an answer. In around February that year, I was contacted by a new game company that had just started up and had barely found their name, The Electronic Generation. A few guys from all over the country were invited to a small meeting. I can’t remember if it was all the way in Jutland, but it was quite far from Copenhagen. The young man in charge revealed the plans to start producing C64 games. The first one would by Golddigger which would be sort of a Boulder Dash clone. One of the invited guys was Klaus, known as Link of Cheyens. It was quickly decided that we would both work on music for the game, using my editor. At that point my NewPlayer version was 5 and Klaus became the first person to use my editor. I remember the strangely content feeling I had when I loaded and played music made in my editor by someone else. Having made a tool that other composers liked to use was a great feeling that I haven’t topped with any other piece of software since.

Tune Nr. 4

What Klaus sounded like in Future Composer, before we met at that meeting.

Breakdown

A tune Klaus made in my music editor, not long after he started using it.

Ironically, the deal with The Electronic Generation fizzled out incredibly fast. Although we made the music for the game, we didn’t hear much more from the company at all. It was as if it had suddenly imploded out of existence. At least the meeting got me acquainted with Klaus, and I was happy about that. He was the composed type that didn’t fool around and our conversions were usually always agreeable. He already had a bit of experience using Future Composer. The funny thing is that the music he made there wasn’t really all that impressive. I think there was only one tune I really liked. But as soon as he started using my editor, I felt that I could immediately detect a significant improvement in the way he composed his songs. It made it clear to me that I was on the right track concerning all the design decisions I had made for the editor.

That was the end of part 2. Click here for part 3.

Thank you, JCH! This is kind of like I’d try to remember how I got my ideas 8 and 10 years later for the AcidTracker. Though my first tracker was a school project in informatics, lasting a whole school year, and it took tons of my spare time. Maybe when I become 50 and want to tell my kids about , I’ll try to review in the same way 😉

Beste Grüße,

Stefan (St0fF/Neoplasia)

fascinate reading JCH. i am so looking forward for the next part. 🙂 you make it to nicely to read.

Very good article 🙂 In 1989 in Poland we could only imagine how A500 looks, so we were delayed in home computers for about 7-10 years, thus very strong C64 users base here. Your editor was very famous among polish C64 demosceners too 🙂

Thanks nice to read this

greets from Holland

Axodry